Ecology of Mourning

A multi media body of work exploring ecology as a framework for processing personal loss.

Click on an image for more details about each piece.

I have been mourning for most of my life, but I’ve only recently realized that most of that time has been spent inactively mourning. The language mental health professionals use to describe mourning is dichotomous—”successful” or ”unsuccessful” as if someone could fail at mourning, but I find this binary—which seems to stem from Freud’s differentiation between mourning and melancholia–problematic. The experience of mourning is vast, and certainly there are different ways to mourn and some may even more effectively address the tasks of mourning—but the experience of mourning is a spectrum that fluctuates. Based on my own experience I’ve come to view the two ends of this spectrum as active and inactive. Active mourning involves the conscious and intentional processing of grief while inactive mourning is attempting to work through feelings of grief that are, for whatever reason, unconscious. Neither is good nor bad and both can result in healing—for me moving into active mourning was a necessary step in my grief work. By doing this, I developed my own ethic of mourning, which I’ve come to call ecological mourning. Ecological mourning uses ecological principles as a framework for understanding and engaging in meaningful mourning. It recognizes that mourning is relational and expansive, that loss necessitates adaptation and reveals dependency, and that allowing ourselves to mourn can help us live meaningfully in a shared, multispecies world.

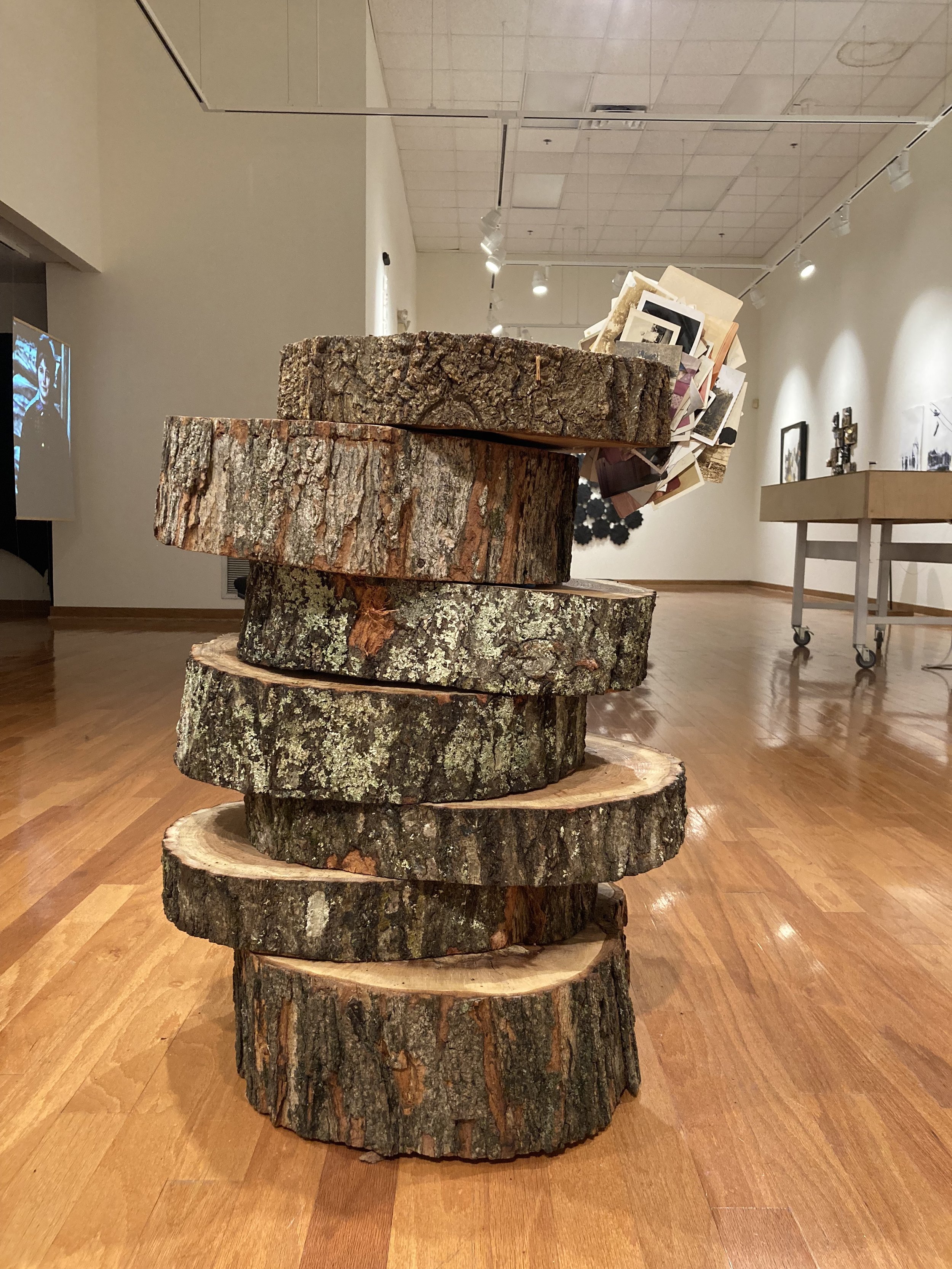

Ecology of Mourning explores this ethic of mourning. It engages in multispecies mourning by memorializing dead tree bodies, turns grief into a physical landscape that can be travelled through, blurs the boundaries between self and other, and confronts both the presence and absence of the body in death. I utilized a variety of materials and processes in creating this work including performance, video, drawing, and sculpture. Several of the materials have specific meaningful connections to my own losses. I use soil collected from the family cemetery where my grandparents are buried, thread from my grandmother’s sewing kit, a piece of tree I held a memorial service for, and found photographs.

Judith Butler says that when we lose someone, not only is the “you” lost, but also some of the “I”, because we have lost some of the ties which constitute us. To anyone who has experienced personal loss, it seems obvious that mourning is relational. Mourning reveals our relationality as it applies to our innermost selves and sense of identity. Our relationships form us; our identities are constructed in part by those who raised us or with whom we interact with regularly and meaningfully. To say I am a product of my mother (or grandmother) is a reference not just to the genetic factors passed down but also the social and cultural ones. We live our lives in relation to others, and so in losing those others we also lose a part of ourselves. Through mourning we must figure out who we are without that person. Ecosystems that lose species adapt. Different species may step in and fill their niche, or the loss might result in changed conditions which creates new niches and allows for species from different environments to migrate in. The pieces that comprise this body of work are the result of acts of intentional mourning through which I have tried to discover how my losses have changed me and how I’ve adapted. They speak to my own grief as well as a shared experience of loss.